Japanese Swords

The Royal Armoury’s collections include a number of Japanese swords that were added to the collections during the 19th and 20th centuries. This might seem strange, but Karl XV in particular was a great collector of weapons. Having weapons from outside Europe also represented in the collections has been common since the 16th and 17th centuries.

The swords in the Royal Armoury can be dated to the Edo period (1603–1867). This was a period of Japanese history that was characterised by peace, but also saw the emergence of a strict hierarchical society during the Tokugawa shogunate. Society was divided into four classes (farmers, craftsmen, traders and samurai), with the samurai class as highest in the hierarchy and thereby the ruling class. As a male member of this class, you were forced to carry two swords, and only samurai were allowed to carry long swords.

This was how you manifested your position in society. The sword was the object that most clearly showed who the samurai was – a warrior and a part of society’s elite. The sword was seen as an extension of him, and was described as the soul of the samurai. As part of this elite, the samurai also had the right to kill someone from a lower social class if they did not behave as expected. Even during peacetime, swords could therefore have a very tangible practical significance – also within the bounds of the law.

Types of swords

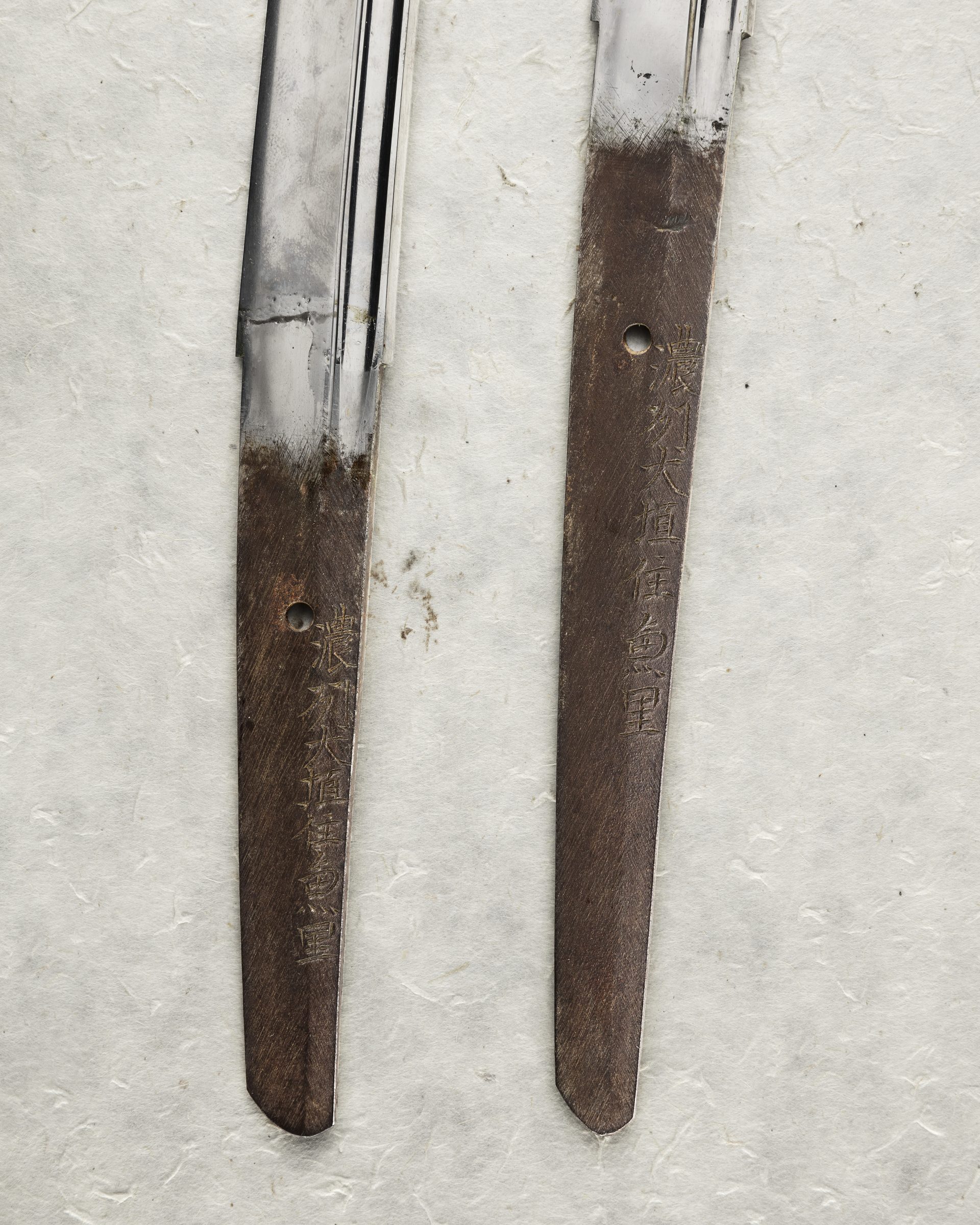

The two swords of the samurai, katana and wakizashi, are together known as daisho and are worn inserted in the belt with the edge facing upwards.

A katana blade is at least 60 cm long and a wakizashik blade is no more than 60 cm. Carrying the sword with the edge facing upwards makes it easier when you want to pull and chop in one single movement, and with its slightly curved, single-edged blade, the Japanese sword is ideal for chopping.

A more archaic way of wearing the sword was to wear it with the edge facing down. This was more practical at a time when warfare was based on the samurai being on horseback. Swords intended to be mounted like this are called tachi and also have a blade of at least 60 cm. Even during the Edo period, swords could be carried in this way in ceremonies and in armour, but not in everyday dress.

The mounting of the wakizashi sword is more consistent with the edicts that existed on how to mount your sword. Daishon has a handachi mount that has more fittings on the scabbard than was usual on a katana. In addition, both swords have an end fitting (kabutogane) that you would otherwise see on tachi swords, and not on katana.

The sword included a knife (kozuka) and a needle (kogai). The knife might be said to be a form of pocket knife, while the needle could be used to eat with or scratch inside the helmet. These smaller items were stored in the scabbard, as the dress at that time did not have any pockets.

From iron to blade

The manufacturing of the most important part – the blade – was a religious act. The forge was purged of evil spirits and the blacksmith lived in celibacy and on a sparse diet, so that he could concentrate on his work. The blade consisted of a tougher core and a harder surface.

The hard surface steel was folded and forged together 13–20 times. The core was folded slightly fewer times. The surface steel was then folded around the core and forged together with it. Folding was necessary in order to purify the steel of phosphorus and sulphur.

Hardening was the most important process. It involved a paste being applied to the blade that had to dry. The blade was then heated and cooled in water. The actual edge cooled the fastest, because the paste had been applied more thinly there. This left a clear trace in the form of a hardening pattern (hamon), which is still visible on many Japanese swords.

To achieve the right finish on the blade, the work was now taken over by the polisher, who polished the blade with sandstones, and finished by polishing it with powder and only their fingers on the already razor-sharp blade. This was followed by the testing of the sword, which could be carried out on bamboo, or on the bodies of executed prisoners.