Gustav Vasa’s Coats in Lübeck

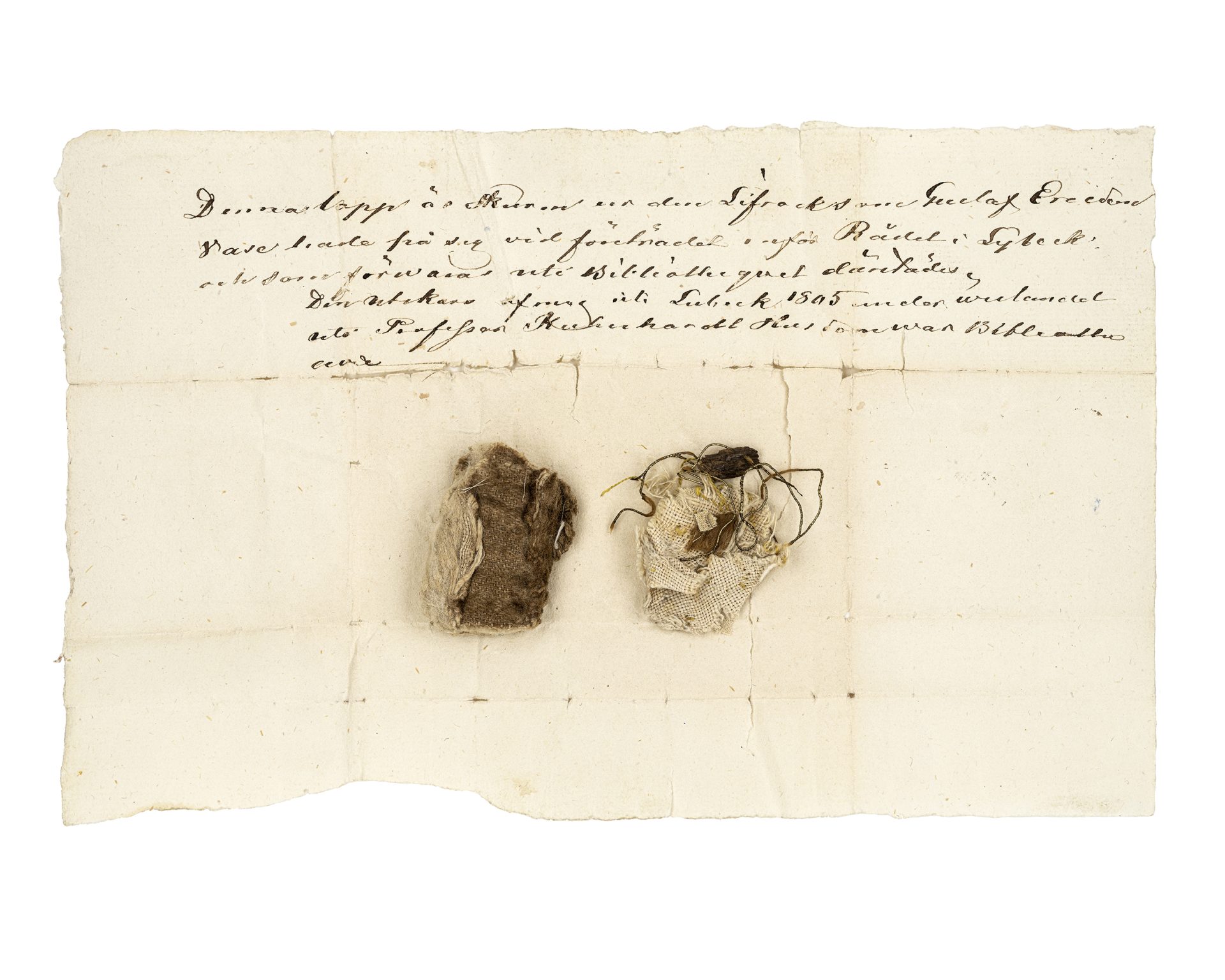

Stored away in the reserve collections of the Royal Armoury Museum lie countless small objects. Some might seem intriguing, others somewhat less so. In a small envelope, for instance, are two badly worn pieces of cloth and a slip of paper. The paper reads:

This scrap is cut from the coat that Gustav Eriksson Vasa wore when he appeared before the Council in Lübeck and which is preserved in the Library there. It was cut out by me in Lübeck in 1805 during my stay in the house of Professor Kuhnhardt, who was the Librarian.

The cloth fragments were cut out by a man named Cassel, possibly Carl Gustaf Cassel (1783–1866). Cassel was staying with the librarian Heinrich Kuhnhardt (1772–1844) when it happened. Is one allowed to do such a thing? And why did he do it?

What happened

When Gustav Vasa became King of Sweden in 1523, the Danes spread spiteful rumours that he was a deceitful and untrustworthy man. They claimed that Gustav had broken his promise not to escape from Danish captivity, and that he had fled disguised as a mere ox-driver. Breaking one’s word and resorting to disguise ran counter to contemporary ideals of honourable conduct.

Gustav Vasa had ended up in Danish captivity in 1519 because the Danish king, Christian II, wished to negotiate peace with Sweden’s regent, Sten Sture. To guarantee the king’s safety, six Swedish noblemen were taken hostage for the duration of the negotiations. Gustav Vasa was among them. The hostages assumed they would remain in Sweden, but they were taken to Denmark against their will.

As was customary at the time, the hostages were allowed a fair degree of freedom in exchange for promising not to escape. Gustav fled Denmark nonetheless and made his way to Lübeck. Once there, he secured the city’s support in his struggle against the Danish king, and the rest is, as we all know, history.

History writing to the rescue!

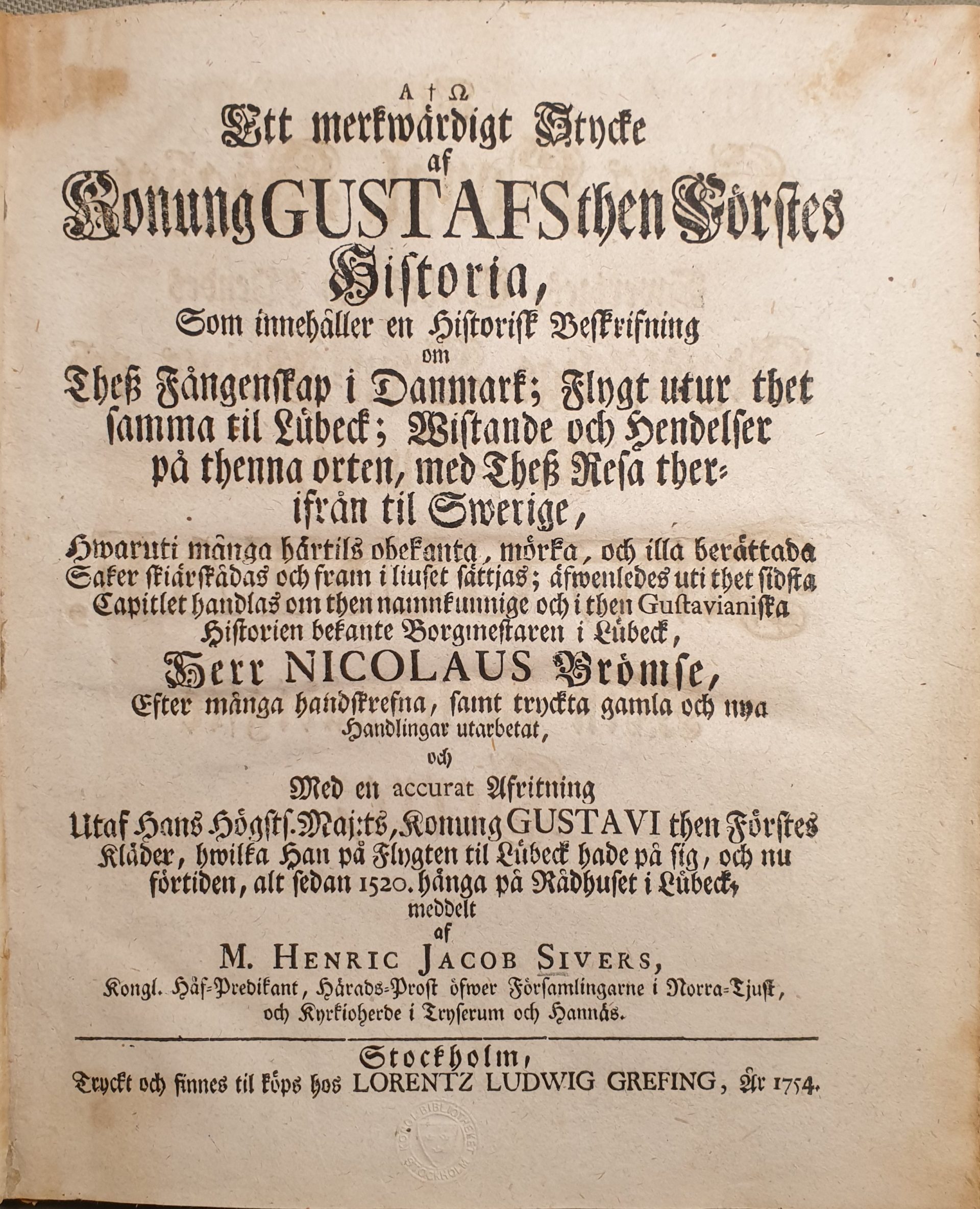

Until 1754, the Gustav’s escape and supposed disguise remained a bone of contention between Danish and Swedish historians. That year, Henric Jacob Sivers published his dissertation A Remarkable Piece of the History of King Gustav the First. His main objective was not to refute the Danish claims. Sivers had a dream: to obtain a Swedish doctorate. To achieve this, he needed to write something that would please both the royal court and Swedish scholars. Thus, he wrote a dissertation on Gustav Vasa’s escape to Lübeck.

In his dissertation, Sivers argued that Gustav Vasa had not been a prisoner at all, but had in fact been kidnapped. The pledge Gustav gave not to flee, Sivers maintained, was invalid because he had been taken to Denmark by force and coerced into making the promise.

The matter of the disguise was harder to gloss over. Sivers therefore launched the idea that Gustav had been clad in two coats, which had since hung in Lübeck’s town hall as a memorial of the event. The coats resemble something a late-15th-century knight might have worn in foot combat. And escaping captivity dressed as a knight was, of course, far more becoming than sneaking off dressed as an ox-driver.

It appears that the story of Gustav Vasa’s coats had been circulating in Lübeck already in Sivers’s youth, as he referred to the coats’ origins as an old truth. But he offered no further evidence. To make the story tally with the fact that there were two coats of the same type, Sivers – incorrectly – assumed that they were meant to be worn on top of one another.

A disastrous result

There is no indication that the coats had attracted any Swedish interest before Sivers’s dissertation. The oral tradition was probably confined to a small circle in Lübeck, if it existed at all. After the dissertation, however, the coats became of great interest to the Swedes.

Sivers’s dissertation had consequences. Most importantly for Sivers himself, he received his doctorate. And Swedish historians gained an advantage in their efforts to “disprove” their Danish counterparts. For the coats, however, the result was disastrous.

Mr Cassel was one of many Swedish tourists who began taking pieces of the coats home as souvenirs. Visitors cut and tore at the garments where they hung in Lübeck’s town hall. Such rough souvenir-taking was common in earlier times. A tourist would often bring back a piece of a famous building or an object belonging to some celebrated figure to show to friends and acquaintances.

A fair amount of the wear we see on historical artefacts today is, in fact, the work of souvenir hunters, including the two 15th-century coats in Lübeck. Compare their appearance in 1755, in 1942 and today.