Three Keris in Detail

A fragmented collection

Modern museum collections are usually based on various private collections from previous centuries. These private collections were usually characterised by a rich diversity and joy of the exotic. But when these collections were nationalised at the end of the 19th century, they were considered too unstructured to be properly managed.

It is for this reason that Swedish cultural heritage underwent a major division around the beginning of the 20th century. Most of the Royal Armoury’s oriental weapons were deposited at the Museum of Ethnography. The time is now right to bring together, at least digitally, these fragmented collections.

Origin and soul

Kris daggers exist throughout the Malaysian archipelago (modern-day Malaysia, southern Thailand, Indonesia, Brunei and the southern Philippines). They have their origins at the end of the Hindu Buddhist period on the island of Java in Indonesia. The kris (keris) used to be both a physical and metaphysical weapon, but its symbolic and ritual aspects are now dominant.

The blade is the actual kris. The hilt and the sheath are merely its “clothes”. Traditionally, the blade of the kris is considered to possess a soul and to be dangerous to possess for those who have not been initiated into how it should be handled and revered. It is considered disrespectful to a kris for it to wear old clothes, which is why these are changed regularly to the current fashion.

For this reason, it is very rare to find krises with hilts and sheaths that date back further than the end of the 19th century in their countries of origin. The krises that came early to the Royal Armoury’s collection have been preserved in their original state. They therefore provide a valuable insight into what krises looked like in their entirety in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Manufacture and meaning

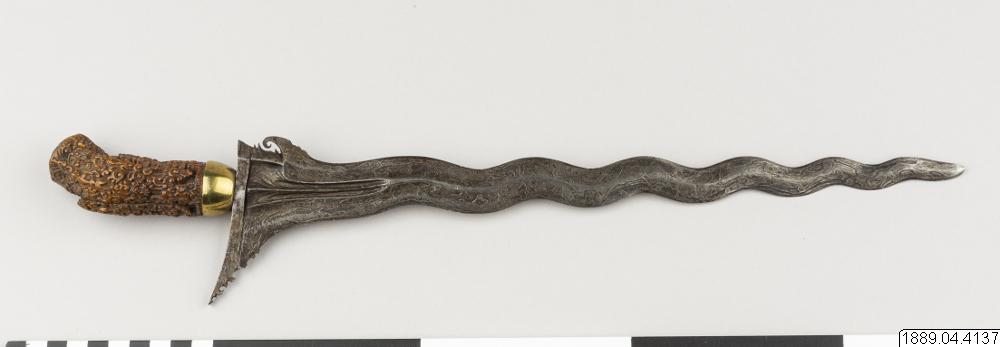

The blade of the kris is made from a mixture of iron and nickel, which the blacksmith folds and hammers in several steps in order to produce different patterns (pamor). By etching the blade with arsenic and citrus juice, the silvery nickel stands out against the black iron, making its pamor appear more clearly.

The blade of the kris is either straight or has an odd number of waves. The straight blade represents the mythological serpent dragon Naga at rest, while the wavy one symbolises Naga in motion. Odd numbers are considered male and even numbers female. Even the traditional Javanese Hindu Buddhist temples have an odd number of roofs. The more waves on a kris or on the roof of a temple, the higher the status of its owner or founding family.

In addition to Shiva and Naga, the elephant god Ganesha is often represented on the blade in the form of a stylised trunk closest to its ganja. Ganesha is both the son of Shiva and a deity who clears all obstacles. The combination of the different shapes and number of waves on the blade is adapted to the personality of the owner. It is considered dangerous to own a kris that does not correspond to your own personality, for example, having more waves than you are spiritually able to manage.

The upper part of the kris’s sheath is shaped like a ship, perhaps inspired by the ships that the former Austronesian sailors once used to make their way to the Malaysian archipelago. Some of the oldest krises in European collections also have painted natural motifs on the sheaths. But they are usually simpler, albeit with beautiful and unusual grains in the wood. They often have a metal casing (pendok) around the lower part, embossed with vegetative or geometric motifs.

A pamor can depict a predetermined pattern or be generated randomly in the forging process. If a random pamor generates a discernible pattern – such as a face, a sitting human figure or an Arabic letter – it is considered to be especially powerful. Usually, a predetermined pamor will also be chosen according to the personality and needs of the owner. There are different pamor that are considered specifically to increase one’s popularity, generate wealth, protect against natural disasters, etc.

The hilts of the kris appear in many different regional and contemporary variants. One characteristic of the oldest hilts from Java is that they clearly represent different Hindu beings, usually Ganesha, Garuda, Durga, Bima, forest spirits (yakshas) or figures from shadow plays. When Islam became the leading religion in Java, these beings were increasingly hidden on hilts, taking on a stylised, barely recognisable form. These figures are usually also sitting on their haunches, in the way they buried their ancestors in the pre-Hindu period.

The kris can be seen as a ritual weapon. And an instrument to reconnect with previous generations in one’s family who owned the kris. It is a portable temple, with whose power one can achieve success in life.

A changing bird

Kris from southern Sumatra, probably from the late 17th or early 18th century. Artefact number 24094_lrk/ETN 1889.04.4094/Karl XV’s collection, oriental weapons, dagger no. 12.

An elephant god

Kris from West Java, probably from the late 17th century. Inv. no.: LRK 24137/ETN 1889.04.4137/Ernst Magnus von Willebrandt’s collection no. 101.

A gilded hero

Kris from north-east Java, probably from the late 18th century, with a gilded Naga (snake dragon) along the blade. (Inv. no.: LRK 23998/ETN 1889.04.3998/Karl XV’s collection, oriental weapons, dagger no. 26.)

This presentation of three krises and their origins is a collaboration with Michael Marlow from Åbo Akademi University and the Museum of Ethnography. Its aim is to offer a small insight into some of the Royal Armoury’s collections.